Sarah Camp, March 2020

PPIs: A Guide to Informed Decision-Making

What are PPIs, and why are they the most effective treatment for GERD?

There are two primary medications with which GERD are generally treated:

- H2 Blockers (Zantac/Ranitidine or Pepcid/Famotidine)

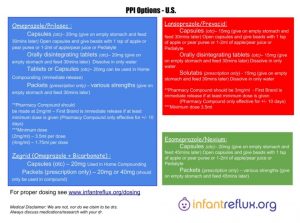

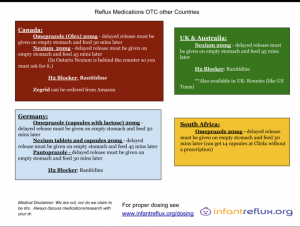

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (Prilosec/Omeprazole, Zegerid/Omeprazole + Sodium Bicarbonate, Prevacid/Lansoprazole, Nexium/Esomeprazole, and Protonix/Pantoprazole)

These medications are both designed to treat GERD, but they function very differently. (Source)

H2 Blockers: Histamine is an inflammatory agent produced by the body, and histamine causes the stomach to produce more acid. H2 blockers stop histamine from reaching the signal receptors of parietal cells, so less acid is produced in the stomach. (The proton pumps are kept from being “activated.”) However, they do not stop acid from being produced altogether. Tolerance is developed quickly to these drugs, particularly by infants. (Source)

Proton Pump Inhibitors: these also reduce the amount of acid produced by the stomach, but they are far more effective than H2 blockers. This is because they bond to the proton pumps that produce acid, and essentially deactivate the cells that produce acid. The body does not build up a tolerance to them the same way it does to H2 blockers. (Source)

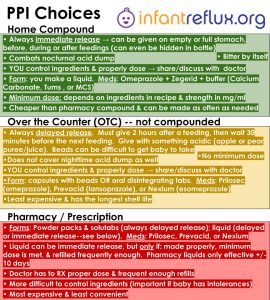

Differentiating Between PPI Choices

The best way to explain the different proton pump inhibitors is that they are all formulations of the same type of drug, as Advil, Motrin, Aleve and Aspirin are all NSAIDs. Omeprazole, Lansoprazole, Esomeprazole, and Pantoprazole are all Proton Pump Inhibitors available in various forms and strengths. The important consideration about selecting a PPI is less about the brand of medication and more about the correct dose, frequency, and form. Omeprazole and Esomeprazole have the lowest recommended effective dose based on our research, followed by Lansoprazole. Pantoprazole requires the highest dosing to be effective. More information on dosing can be found here.

Prescription compounded liquids: Omeprazole (2 mg/ml), Lansoprazole (3 mg/ml)

Prescription packets: Omeprazole, Nexium, Zegerid (various strengths)

Prescription solutab: Lansoprazole (15 mg)

Over the counter capsules: Omeprazole (20 mg), Zegerid (20 mg), Lansoprazole (15 mg), Nexium (20 mg)

Over the counter disintegrating tabs: Omeprazole (20 mg), Lansoprazole (15 mg)

Over the counter tablet: Omeprazole (20 mg)

All over the counter purchased materials by themselves are delayed release, as are the prescription solutabs. This means they must be given on an empty stomach (about 2 hours after finishing a feeding), and then followed by a meal 30-45 minutes later. (Source)

Prescription compounded liquids have the ability to be immediate release only if made correctly and minimum dose is met. These solutions also begin to lose potency after about 10 days. More info here: FirstBrand notes for pharmacy compound

An immediate release compound can be made at home by using over the counter materials. Medications for this include Zegerid, Omeprazole, and a buffer such as Tums or Calcium Carbonate. Zegerid must be used in any immediate release compound for the sodium bicarbonate it contains, and Omeprazole is the easiest drug to use in combination with it. (Zegerid already contains 20 mg of Omeprazole, so another 20 mg Omeprazole is the easiest number to work with for home compounding recipes.) Research proving the effectiveness of immediate release can be found here.

A bit of background information about our personal story:

When we first began our reflux journey, we were at the pediatrician at least once a week. I might as well have had my own parking spot. The nurses were clearly annoyed with me each time I called asking my five-millionth question or requesting ANOTHER appointment. We started on Zantac, increased dose, switched to hypoallergenic formula, then were put on an unbelievably low dose of Omeprazole. On a subsequent visit, I was told my baby just had colic. COLIC! (There is no medical diagnosis called ‘colic.’ It’s a doctor’s way of saying “your baby cries a lot and we don’t know why. Sorry but we can’t help you. Hopefully it will get better soon; now off you go!”)

I was beyond thrilled to finally get in with a pediatric gastroenterologist. I went in with my notes, research, proper dosing calculations, everything. I had a baby who cried non-stop and my mom gut just KNEW something was wrong. A GI could help us, right? Imagine the soul-crushing discouragement I felt when the doctor told my husband and me that PPIs aren’t effective, that my baby was just fussy and needed to grow out of it, while asking her “why was she causing so much trouble?” She also said that my child must have a low pain tolerance and made this comparison: it’s just like how some mothers have a very high pain tolerance during delivery and can deliver naturally with no medications, while others need pain medications or an epidural to get through it. HELLO, she clearly just admitted that my baby was in pain and refused to do anything about it! I’m shocked that I actually made it to the parking lot before dissolving into a puddle of tears.

At our next appointment (with a different doctor, of course), we were thrilled to have our near-placebo dose of Omeprazole increased to *twice* a day. And when the well-respected physician who founded the most reputable and longest-standing pediatric GI practice in our large metro-area suggested we thicken our daughter’s bottles with oatmeal (without a swallow study, no less), I was easily persuaded because surely HE must have all the answers, right? Wrong. After seeing my baby girl in pain and continuing to deteriorate, nearing dehydration and well on her way to a full-blown feeding aversion, I knew I was going to have to take matters into my own hands. By our third opinion appointment, I was ready to go in telling the doctor what I was ALREADY doing, explain the research I had to back it up, and advocate for what my daughter needed (as well as resist any treatments I knew would be unwise for her).

I cannot stress enough how vital it is for you as a parent to do your own research and take ownership of your child’s medical care. Are you a doctor? Probably not. Am I a doctor? That’s a definite no. BUT I am capable of doing research, and so are you. Find a doctor who will listen to you, who will be your teammate in your child’s care. I can all but guarantee that you are far more interested in and devoted to the treatment of infantile acid reflux than nearly any medical provider you will ever come in contact with. Why? Because you have a vested interest in fighting for your baby and doing everything in your power to help them be healthy and feel better. When your doctor quotes you a study as to why they are making their recommendations, but you don’t think it is safe for your baby or that it will help them, ask them for their sources. They should at the very least be able to provide you with the title and authors of the research. Better yet, ask them if they can provide you with a copy of it!

At first I broke down and paid for one of the articles commonly cited, the one that I’m sure our first GI was quoting to me ($36.95…ridiculous!). This is one that is surely being referred by doctors around the globe that PPIs aren’t effective in infants, because it’s one that is discussed by the FDA as to why most PPIs are not approved for use in children younger than 12 months due to not being effective. The study was completed on infants 3-12 months and was published almost 20 years ago (2002) in Australia. I can’t post the article in its entirety due to copyright laws, but I will link it below so that you can purchase it yourself if you would like to read the whole thing in context. Let’s take a look at some of the highlights (and in my opinion, flaws) of the study.

[Moore, David & Tao, Billy & Lines, David & Hirte, Craig & Heddle, Margaret & Davidson, Geoffrey. (2003). Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of omeprazole in irritable infants with gastroesophageal reflux. The Journal of pediatrics.]

“At entry, no infant had been investigated for GER, and all were thriving.”

“…infants from 5 to 10 kg were given 10 mg daily and >10 kg were given 10 mg twice daily.”

“None of the infants had been given an empirical trial of proton pump inhibitor before recruitment.”

“There were no reports of adverse events from treatment with omeprazole or placebo.”

“All infants while taking omeprazole had a reflux index of <5%…whereas 5 of 15 taking placebo had a reflux index of >5%.”

“There was no significant difference in the cry/fuss time while taking either omeprazole or placebo…However there was a significant fall in cry/fuss time from baseline to period 1…There was no significant decrease in cry/fuss time between period 1 and period 2.”

“The 15 infants who met the biopsy criteria for esophagitis were compared with the 15 infants with normal esophageal biopsy specimens, and no difference was found for baseline cry/fuss time…Furthermore, the 15 infants with abnormal esophageal biopsy demonstrated no difference in response to omeprazole vs placebo.”

“The VA [visual analog] score assessed by parents for the level of irritability in their infants while taking omeprazole or placebo was not significantly different.”

“In this trial of omeprazole, no adverse events were recorded, and it was highly effective in reducing acid exposure in infants 3 to 10 months of age.”

“Despite effective acid suppression in infants with GER, omeprazole failed to suppress symptoms of irritability; it is possible that non-acid reflux may be related to the irritability of some infants with GER.”

“Hill et al have suggested that food protein intolerance in infants could be another cause of esophagitis leading to infant distress.”

In short, the trial here was ONLY looking at crying, not pH or any other symptoms like feeding refusal, arching, Sandifer Syndrome, etc. Crying is not the only concern of acid reflux, nor is it the only goal to be reduced. Some mention of this is made with the reflux index, which does indicate that the treatment was at least somewhat effective in reducing actual reflux.

The dosing here was not only not given as frequently as recommended but also under-dosed. Crying may not have improved because pain did not improve. This is further proved by the fact that the infants with esophagitis did not improve on the dose given; it wasn’t sufficient to raise pH enough or for a proper amount of time to allow healing.

The reason that infants responded better at the first part of the trial than the second could be due to the “honeymoon effect” when starting a new medication or something changes in diet. Things get better at first before they get worse again until the correct treatment is finally found.

Food intolerance is also mentioned. It is important to note that food intolerances can cause histamine reactions in the GI tract, which in turn produces acid.

Finally, it was acknowledged that there were no adverse reactions to the PPI.

After seeing this one article, I became interested in doing further research on the efficacy and safety of PPIs, specifically omeprazole since that’s what I’ve had my daughter on for over 6 months now at and above what is considered “Proper Dosing.” I wasn’t willing to continue spending that amount of money on research, but thankfully our phenomenal family physician told me about PubMed. This is a free database that houses millions of medical journal articles and studies. Usually the full texts aren’t available for free, but detailed summaries are; the quotes I have copied below come from the abstracts of the articles. I have included links as well as citations to each excerpt underneath. If you have concerns about PPIs or simply want to learn more, please read through them and educate yourself. There is no one who can make decisions for your baby better than YOU, as long as you are well-informed!

It seems to me that doctors typically cite one of four reasons that they either won’t prescribe a PPI at all, or won’t put babies on proper dosing:

-

PPIs aren’t proven to be effective in infants.

-

PPI dosing has to be low.

-

PPIs have too many risks.

-

The FDA has not approved most PPIs for use in infants.

1. “PPIs are not proven to be effective in infants.”

PPIs are most certainly effective in infants, if dosed at the correct strength and frequency. I am speaking from personal experience with my own child, as well as so many other mothers in our group. The reason that some studies have found PPIs to be ineffective is because A. the participants were not being properly dosed, and B. the criteria being measured were not representative of true reflux control. At the very least, the PPIs reduced the amount of acid in participants’ upper GI tracts. The first set of quotes support the efficacy of PPI therapy in pediatric patients. The second set suggests that the effectiveness of PPIs in pediatric patients is questionable; beneath those I will highlight why the studies are misleading.

Click here for a printable file of research on the efficacy of PPI use in infants.

2. “PPIs must be given to infants at low doses.”

For a majority of pediatric patients, a once-daily low dose of an H2 Blocker like Pepcid or a PPI like Prilosec may be effective, and the patient may need no further treatment. Please hear me when I say this: if your child is thriving on that dose of that medication, by all means keep it that way! There is no need to medicate a child (or anyone) who doesn’t actually need it. Most people who end up here looking for resources and support have babies with severe GERD, and these conservative treatments have failed for them. Babies absolutely should not continue to be in pain. If that is the case, then something needs to change.

In our case, even on these standard treatments, our daughter was still in a tremendous amount of discomfort. As mentioned somewhat in the research compiled on the efficacy of PPIs, a significant reason that PPIs could be found ineffective in infants and even the pediatric community as a whole is due to improper dosing. Patients may not be dosed correctly based on not only weight but also age. Dosing may not be frequent enough for how quickly younger patients’ bodies eliminate the drug. Furthermore, some newer research indicates that different genetics within each patient may affect how PPIs are metabolized, and dosages may need to be adjusted accordingly.

Click here for a printable file of research on how PPIs should be dosed for infants.

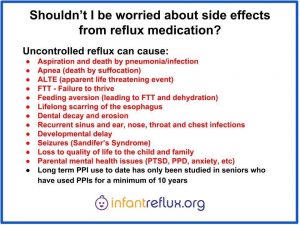

3. “PPIs have too many risks.”

PPIs, like any medications, do have potential side-effects. In most studies on infants and children, they were deemed to be well-tolerated. Limited data suggests some correlations to respiratory or GI infections, common symptoms like headache, and a few other adverse events. I have included all available research on these, both positive and negative. Some other research discussing acid rebound when coming off of a PPI has recently come to light. There was only research for this available for adults.

A risk vs. benefit analysis is always crucial when considering medication. When my child screamed incessantly in pain, had clear spit-up that smelled horrible and dried orange (acidic, possibly bloody), wasn’t gaining weight, started developing a feeding aversion, would stop breathing in her sleep while she was refluxing, and couldn’t have any decent length of sleep, the chance of side effects was worth it for us personally to bring her much-needed comfort, not to mention nutrition/weight gain. It is imperative that you consider all of these factors and discuss them with your medical team when making your own decisions for your child.

Click here for a printable file of research on side effects of PPIs for infants and children.

4. “The FDA hasn’t approved most PPIs for use in infants.”

There simply isn’t enough data available for the FDA to approve all PPIs for use in infants. The data that does exist is neither controlled nor widespread enough. Personal experience from our own children as well as helping other moms tell us that PPI use in infants is effective when proper dose and frequency is followed.

Click here for a printable file of research on why most PPIs aren’t approved by the FDA for use in infants.